by Kristine Schmucker, HCHM Curator

We have heard many references to the “Spanish Flu” or the “Flu Pandemic of 1918” comparing it to the current COVID 19 pandemic. Usually the focus is on what happened at the national level in 1918, but what was it like in Harvey County.

National Response in 1918

In October 1918, the American Red Cross mobilized their nursing services, which included supplying nurses and covering their salaries and other expenses. They worked with doctors and local governments. Soon, the Red Cross was part of a national coordinated strategy, which included the U.S. Public Health & Services and the U.S. Surgeon General, to deal with the Influenza.

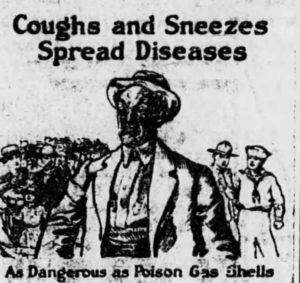

An October 15, 1918 article in the Evening Kansan Republican, gave “Uncle Sam’s Advice on Flu” urging people to “guard against ‘droplet infection’.”

Even comparing “coughs and sneezes . . .as dangerous as poison gas shells.”

The same article revealed that much was not known about the disease and, at first, it was not recognized as a virus.

On November 2, 1918, the U.S. Public Heath & Services reported 115,000 deaths from influenza and pneumonia.

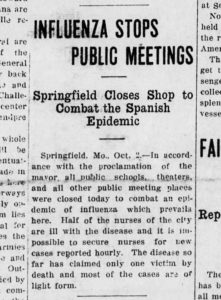

National headlines announced the closure of public meetings across the country.

Kansas

In Kansas, the Influenza affected the entire state. Early in October, schools were closing.

By October 8, universities, including the University of Kansas, closed and “all visitors refused at Institutions” as the epidemic spread rapidly across Kansas.

Harvey County in the fall of 1918 was focused on the war in France, war bonds and “the Flu. A search of the Evening Kansan Republican revealed that the “Influenza” or “Spanish Flu” was mentioned daily October through December 1918. Using newspapers and a collection of letters written by Waive Kline, we can get a glimpse of what life was like in Harvey County for three months during the Influenza Outbreak of 1918.

“Be good and don’t get the ‘Flu.’ With love, from Waverly”

Waive Kline was 26 years old in 1918, living on a farm in Macon Township in Harvey County with her parents George and Linnie Kline.

Both, Waive and her sister Grace, had attended Bethel College and taught at nearby one room schools at different times. Her brother, Maurice, was in the navy.

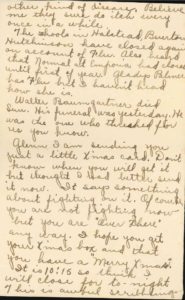

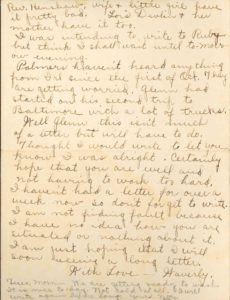

Waive’s fiance, Glenn Wacker, was in France with the Tank Corps during the fall of 1918 and her letters during the period of October to December 1918 show a picture of the uncertainty, the lack of information and life in Harvey County during a tense time. Although she touches on a number of subjects in her letters, this post will focus on “the Flu.“

Stopping the Flu

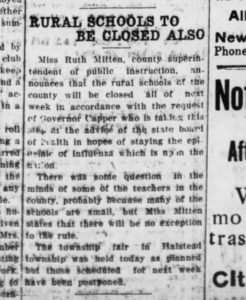

Early in October local schools followed the recommendations of the Kansas Governor and closed in an effort to stop the disease.

Waive noted:

“It [the Flu] is certainly spreading around here. All schools and almost everything else are closed and will be all of next week and probably longer”(11 October 1918, Waive to Glenn)

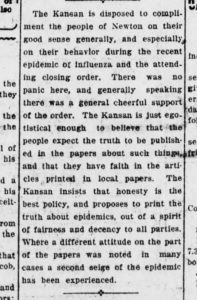

Apparently residents of Harvey County took the “closing orders: seriously. In November the editor of the Evening Kansan Republican “complimented the people of Newton on their good sense . . . during the recent epidemic . . . and the attending closing order. There was no panic here . . . and a general cheerful support of the order.” (Evening Kansan Republican, November 30, 1918)

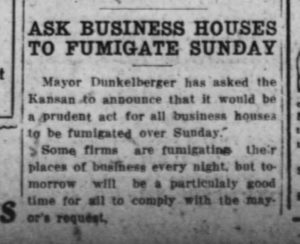

Other efforts to combat the spread of the disease beyond the “closing orders” included fumigation.

Waive mentions fumigation in Newton as the community worked to combat the epidemic.

“I have been afraid to go on account of the “Flu.” They fumigate every day and the way it smells I hardly think the germs would care to stay in there.” (“November Moon” 25 November 1918, Waive to Glenn)

Entire families were critically ill. The November 20 edition of the Evening Kansan Republican reported the sad news of the death of Ernest L. Fulton, principal of the Lincoln School in Newton “from the effects of influenza” He had been sick for about a week. His wife and “little daughter” were also very ill.

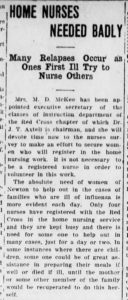

In mid-October the doctors in Newton made a plea “to the women of Newton to help out in the cases of families who are ill of influenza . . .even a single afternoon or to remain over night to give a tired worn out mother a chance for a night rest, it would be the highest duty and the best service she could render.”

Mt. Pleasant

Waive letters reveal concern for local friends and neighbors in the Macon Township community of Mt Pleasant.

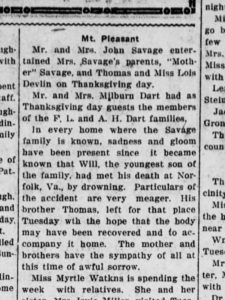

She often included snippets of information about neighbors, especially the Savage family, which would experience so much heartache in the coming months.

“I guess it isn’t so quite so bad if a person takes care of himself. Glenn Palmer is in the hospital . . . Willie Savage also has it.” Be good and don’t get the ‘Flu.’ With love from Waverly. ” (11 October 1918, Waive to Glenn)

In addition to the “Flu,” many families like the Finnell family worried about sons in France.

“You know Charlie Finnell is pretty bad, sick, with influenza. We are trying to be very careful so we don’t get sick. You must do the same.” (20 October 1918, Waive to Glenn)

In the same letter, Waive mentions that Charlie’s brother Loren Finnell had been reported dead.” (20 October 1918, Waive to Glenn) The rumor that Loren Finnell had died in combat turned out to be true.

“Print the Truth About Epidemics”

Accurate information was often hard to come by. The local paper, Evening Kansan Republican, was the main source for outside information. In a letter dated October 25, Waive noted that Mr, Hogan had died, only later to learn he actually recovered from the flu.

“The way the paper talks there won’t be any school next week. I think it is a good idea. The flu is pretty bad in Newton . . . Mr. Hogan (the proprietor of the Racket Store) died this p.m. The rest of the family have but are better. That is what we heard. (25 October 1918 Waive to Glenn)

The Evening Kansan Republican worked hard to provide accurate information, even though facts were sometimes slow in coming. Accuracy was a point of pride for the editor. He noted, “The Kansan is just egotistical enough to believe that the people expect the truth to be published in papers . . . and they have faith in local papers. The Kansan insists that honesty is the best policy, and proposed to print the truth about epidemics.”

“About All You Hear These Days Is “Flu.”

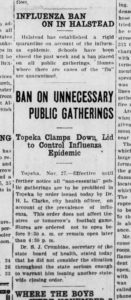

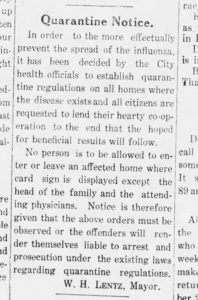

By the end of November there were again “bans on unnecessary public gatherings” in certain areas of Kansas. Even though Dr. S.J. Crumbine, secretary of the state board of health did not feel “the situation throughout the state serious enough to warrant . . . another statewide closing order.” The city of Halstead did “establish a rigid quarantine” and several area schools closed.

The schools in Halstead, Burrton, Hutchinson have closed again on account of the Flu” (Nov 30, 1918 Waive to Glenn)

“About all you hear these day is “Flu.”It is pretty bad again but seems to be in somewhat milder form than when it first started. There are a number of cases around here. . . .Rev. Henshaw, wife and little girl have it pretty bad. Lois Devlin and her mother have it too.” (9 December 1918 Waive to Glenn)

Lois Devlin, another Mt. Pleasant neighbor, initially seem to recover, however she died of complications from the flu in July 1921 at the age of 26. In the same letter, Waive noted that the Palmer’s still had not “heard anything from Art since the first of October.”

“It Is Worse Now Than It Has Been Any Time”

In December even more people became ill, so many that Waive noted “it takes too much time” to list them all.

“Melvin Savage came home on furlough. He got the flu and day before yesterday they took him to hospital. He has pneumonia now and is very sick. They have never found out anything more about Willie. Lois D. has the flu, also Florence Michael. I could name a whole lot more but it takes too much time.” (13 December 1918, Waive to Glenn)

The Savage family lost two sons in a short time, William by drowning and Melvin from the Flu.

Waive noted:

“One thing certain it is very bad. Seems to be just thick every where. We have escaped it so far and are going to try to keep on escaping it. You said in your letter that the flu would be over by the time I got your letter, but I guess it is worse now than it has been any time. A good many people are just having it in a mild form while others are very bad.” (13 December 1918, Waive to Glenn)

During the months of November and December, Waive stayed on the farm and helped her father. With her brother in the navy, her sister teaching and her mother not well, it fell to Waive to help with the farming chores throughout the winter.

Waive and Glenn married October 30, 1930 and lived their lives in Newton, Ks. Waive died in 1984 and is buried in Greenwood Cemetery, Newton, Ks. Her letters are part of the Wacker Family Document Collection and can be found at the Harvey County Historical Museum & Archives, Newton, Ks.

The Influenza & Public Health

People continued to struggle with the Influenza into 1919. A January 1919 “Nurse’s Report” in the Evening Kansan Republican highlighted the on-going struggle with the disease with 94 cases of Influenza.

The Influenza of 1918 changed the way health care was viewed—especially public health. The Flu led to a greater understanding of disease, transmission and public education. In the early 1920s, in Harvey County there was a desire for better care for the community and the first Public Health Nurse, Sister Anna Gertrude Penner, a Mennonite Deaconess, was hired. One of her jobs, beyond providing care, was education especially for the poorer people in the county. The leaders of this movement in Harvey County included women from two different faith traditions, Lillian Fitzpatrick and Johanna Conway from St. Mary’s Catholic Church along with Sister Anna and the Bethel Mennonite Deaconesses.