by Kristine Schmucker, HCHM Curator

For more about Hugh Anderson in part 2.

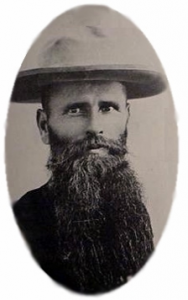

We just passed the 144th anniversary of Newton’s famous gun fight and there are still interesting pieces of fact and fiction that surround the event. While researching the actual gunfight, I became interested in the men that reported on the event. One reporter, in particular, was quite descriptive and detailed, but I could not find out more about him. He signed his work as “Allegro” and was a correspondent for the Topeka newspaper, The Commonwealth. Recently, I stumbled on some newspaper articles that shed a light on the mysterious reporter, Allegro, and the eventual fate of Hugh Anderson.

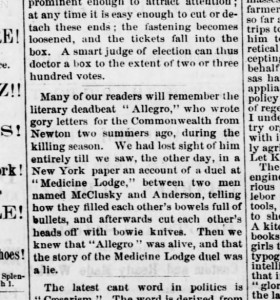

The Junction City Weekly Union paper reported in August 1873:

“Many of our readers will remember the literary deadbeat “Allegro” who wrote gory letters for the Commonwealth from Newton two summers ago, during the killing season. We had lost sight of him entirely till we saw, the other day, in a New York paper an account of a duel at “Medicine Lodge,” between two men named McClusky and Anderson. . . . Then we knew that “Allegro” was alive, and that the story of the Medicine Lodge duel was a lie.” (Junction City Weekly Union, 16 August 1873, p. 1)

This small article led to all sorts of interesting discoveries, some that gave clues to who Allegro might be and also what really happened to one of the main players of Newton’s Bloody Sunday.

A Correspondent named “Allegro”

In a May 2, 1878 letter to the editor, a “Citizen” reflected on the “old Commonwealth crowd” of editors and reporters mentioning “Allegro who wrote those blood-curdling letters from Newton” and “who ought not be forgotten.”

According to the letter, Allegro was a “mild-mannered, gentlemanly fellow, but a beat of the first water.” During the summer of 1871, Allegro spent time as a fiddler in one of the Newton dance halls, in addition to serving as a correspondent for the Topeka Commonwealth. He was finally “bounced [from the Commonwealth] because he took up too much space puffing the saloons where he got his drinks.” From there, Allegro went on to write “lurid sketches of frontier life for the New York World.” One of those “lurid sketches’ was the story of the duel between Hugh Anderson and Arthur McCluskey in 1873 that the Junction City Weekly Union called a lie.

Late in 1873, the New York World cut ties with the correspondent identified as “Allegro.” According to the New York World he was “a shyster named E.J. Harrington” living in Washington, D.C. who was “utterly unworthy of confidence or countenance” and belonged in the penitentiary.

The Duel. . . according to ‘Allegro:’ A Short Summary

Allegro submitted the story entitled “Meeting of the Desperadoes Hugh Anderson, of Texas and Arthur McCluskey of Kansas,” which was printed July 22, 1873. He claimed to be an eyewitness to the event.

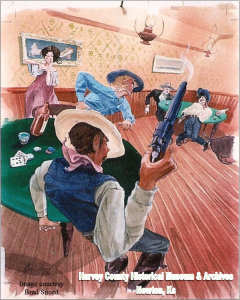

According to his account, Art McCluskey, the reported brother of Mike McCluskey, who was killed in Newton by Anderson, arrived in Medicine Lodge, Indian Territory in July 1873 with revenge on his mind. At Harding’s Trading Post, Art McCluskey challenged Hugh Anderson to a duel with “revolvers and bowie-knives.” The two met at the agreed upon place along with “at least seventy spectators.” McCluskey was the first to fire, hitting Anderson across the cheek. McCluskey was also hit in the chest. Soon both men were mortally wounded and out of bullets.

“McCluskey, summoning by a supreme effort his remaining strength, drew his knife and began to crawl feebly in the direction of his antagonist. The latter, who had raised himself to a sitting position saw the movement and prepared to meet it.”

Both men proceeded to hack at each other until the end. According to the article, “McCluskey lived a minute longer than his antagonist. The dead bodies, firmly locked in each other’s embrace.”

The clipping from the Junction City Weekly Union raised questions about this story.

The Death of Hugh Anderson: The Duel that Never Happened.

In December 2014, researcher Douglas Ellison dug deeper into the facts surrounding the “duel to the death” between Art McCluskey and Hugh Anderson in Medicine Lodge. According to Ellison, the story of the duel at Medicine Lodge, Indian Territory was widely discredited in 1873, including in Newton. The editor of the Newton Kansan, H.C. Ashbaugh, had misgivings, even though he reprinted parts of the story on the front page on August 7, 1873.

Ashbaugh did mention his doubts about the truth of the story on page 3:

“As to the truth of the transaction we are at doubts, since no person in this region of country appear to have known anything about it until this made its appearance. The events leading to the story, be it true or false one, originated for a fact in Newton.”

One of the most glaring issues is the place where the duel took place. The author described the duel taking place at “Medicine Lodge is in the very heart of the Indian nation, about a hundred miles south of the Kansas frontier.”

The problem, no such place existed in Indian Territory.

An assumption by later storytellers was that the duel took place in Medicine Lodge, Kansas, and the author of the original tale made a mistake. However, the author of the story goes to great lengths to describe the place as being in the “very heart of Indian Territory.” The editor of the Junction City Weekly Union expressed skepticism at the time regarding the place of the alleged duel and called the whole story a lie.

“we saw, the other day, in a New York paper an account of a duel at “Medicine Lodge,” between two men . . . the Medicine Lodge duel was a lie.” (Junction City Weekly Union, 16 August 1873, p. 1)

In addition to other problems with the story, the account was never corroborated by any other contemporary source even though, according to the article, “at least seventy spectators” watched the duel. In fact, local papers did not even know about the story until three weeks later. Especially in Newton, the site of the original gunfight in August 1871, the news of a duel involving the one of the principle shooters should have gotten more response.

Despite the skepticism of the time, the story somehow gained credibility. Over the years, both casual and serious historians, were somehow “gulled into believing and perpetuating a false myth of murder and revenge” described by “Allegro.” (Ellison, p. 10) Ellison acknowledges that even though the story “made good reading in 1873, and it makes good reading today,” it is still false.

We don’t know what happened to E.J. Harrington, aka “Allegro.” The last mention found so far, was in the Commonwealth letter to the editor where “Citizen” concludes, “the last I heard of him, he was in Washington, where he struck Hon. S. A. Cobb for a small loan. He maybe in Congress now for aught I know.” (Daily Commonwealth, 2 May 1878)

Our post next week will look into what did happen to Hugh Anderson and the resulting proof that the story was made up by the Allegro/Harrington.

Sources

- Fort Scott Monitor (Fort Scott, Ks): 12 Nov. 1871, p. 4.

- Lawrence Daily Journal (Lawrence, Ks): 18 January 1872, p. 2; 20 December 1873, p. 3.

- Newton Kansan (Newton, Ks): 7 August 1873 , p. 1 & 3: 14 August 1873, p. 2.

- Junction City Weekly Union (Junction City, Ks): 16 August 1873, p. 1; 14 February 1874, p. 2.

- Daily Commonwealth (Topeka, Ks): 2 May 1878, p. 2.

- Ellison, Douglas. “The West’s Bloodiest Duel-Never Happened!” Western Edge Books, 3 December 2014 at westernedgebooks.com. The article, “Meeting of the Desperadoes Hugh Anderson, of Texas and Arthur McCluskey of Kansas,” featured in the New York World, 22 July 1873 (p. 2 ) written by J.H.E. correspondent for the New York World, was reprinted in its entirety in Ellison’s article.

For the full article by Douglas Ellison see The West’s Bloodiest Duel – Never Happened. He also investigates several other problems surrounding the tale.

![Gunfight_note[1]](https://hchm.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Gunfight_note1-265x300.gif)