by Kristine Schmucker, HCHM Curator

On September 7, 1862, the men of the 86th Illinois marched out of the gates of Camp Lyon, through the streets of Peoria with great fanfare to the train depot. There they joined the 85th and boarded the train for Camp Joe Holt, Jefferson, Indiana. Among the men in the 86th was 20 year old John W. Burns. Described as being 5′ 8″ in height with light complexion, dark hair and hazel eyes, John had volunteered a month earlier with the Union army. He listed his occupation as a farmer.

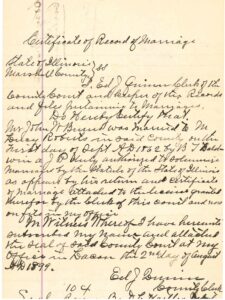

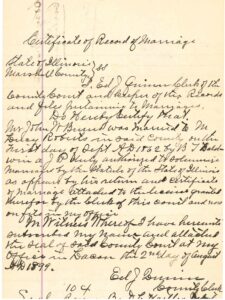

Six days before he left, on September 1st, 1862, he married Zelpha L. “Lucy” Roberts in front of Justice of the Peace T. Baldwin in Marshall County, Ill. According to later statements they had known each other since childhood.

Certificate of Record of Marriage, John W. Burns Civil War Pension File.

Three weeks later, John was a part of Col. Daniel McCook’s Brigade pursuing Confederate soldiers. At the Battle of Perryville, Kentucky, the 86th Ill suffered their first casualties.

Over the next two and a half years Private John W. Burns was witness to and a participant in numerous battles, including some of the bloodiest fighting in the Western Theatre including the Battles of Chicakauga, Resaca, Rome, Peach Tree Creek all in Georgia, and Aversborough, N. Carolina. John was also along with Sherman on his infamous “March to the Sea.”

Sherman’s March to the Sea.

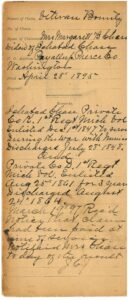

Toward the end of the Civil War, John was injured and sent to a hospital near Camp Butler, Springfield, Ill. PVT John W. Burns was discharged on May 2, 1865 and he returned to his home in Marshall County, Ill. He picked up the pieces of his life with his wife and resumed farming. John and Lucy had one child, Herbert H. Burns, born September 21, 1865.

The Burns family came to Harvey County, Ks in 1877 and settled to farm two miles northwest of Sedgwick, Ks.

There are not many clues as to what kind of person John Burns was prior to volunteering for the Union Army, but his time fighting had an affect on him. By the mid-1880s, Burns began to have difficulties as a result of injuries received during the war including rheumatism. He also became violent toward his wife, Lucy.

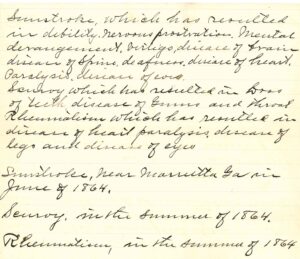

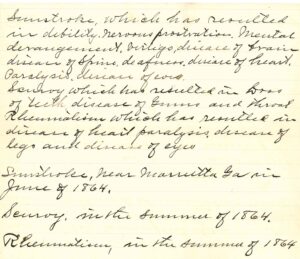

In 1892-3, he applied for a pension. The list of ailments that John Burns suffered from was included in his file. Sunstroke which happened “on or near Marietta, GA, June of 1864” and resulted in many problems including derangement, vertigo, disease of brain, heart paralysis. Scurvy and rheumatism in the summer of 1864 also caused problems later in life.

John W. Burns List of Afflictions

In March 1893, he began receiving a pension of $30.00 a month “on account of disease of heart and nervous system, result of severe stroke . . . and rheumatism.”

“Is not Inclined to Take his Incarceration Easily”

January 1, 1899, Lucy left their home in fear for her life in the middle of the night. The story of the abuse endured by Lucy was chronicled in John W. Burns’ Pension File. Between the documents in the file and the newspaper, a very grim story emerges of the last years of John’s life.

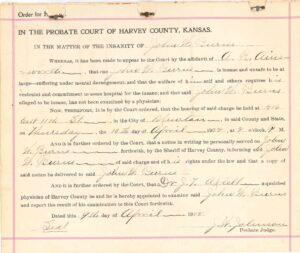

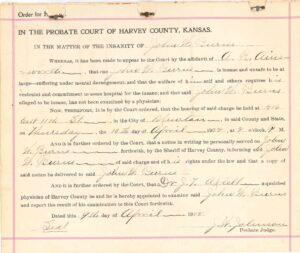

On April 10, 1902, Burns was judged to be insane. Since Harvey County did not have a facility that could take proper care of him, John stayed at Axtell Hospital where a male nurse was with him constantly. The Evening Kansan Republican concluded that “Mr. Burns is not inclined to take his incarceration easily and at times makes trouble for the attendants.”

At the end of April, he was transferred to the Asylum in Topeka, where he died a short time later on April 26, 1902. His obituary noted that he was one of the earliest settlers of Harvey County, an “old soldier” and “a well known character . . . however in the last years of his life he was afflicted with poor health and under the strain his mind gave way.” (Evening Kansan Republican, 26 April 1902.)

“I am the lawful widow of John W. Burns”

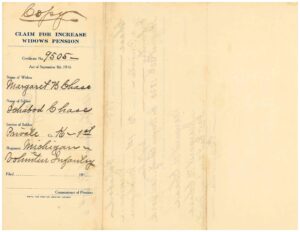

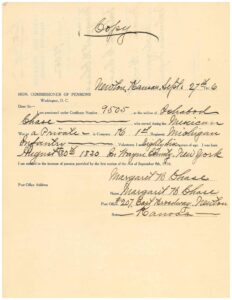

As the widow of John Burn, Lucy Burns was eligible to continue to receive his pension. However, she had to have documented proof that she was “the lawful widow of John W. Burns.”

The pension file of John W. Burns tells the tale of a mentally ill man and the abuse endured by his wife.

Lucy Burns, 55 years old, described the events that led her to separate from her husband in 1899.

“My husband, John W. Burns, commenced to abuse and ill treat me some two or three years ago. . . .One night in December 1896, he walks the floor all night long with a flat iron in his hand and he threatens to kill me. He has not supported me for the past fifteen years . . . the night I finally left him was January 1st, 1899, he pounded me with his fist and he threw me out of the house and then locks the door, so that I could not get in.”

Mrs. Burns went to a neighbors and did not go back.

“I am the wife of their only son”

Lucy’s daughter in law supported Lucy. Kate Burns, age 31, noted that she had known John and Lucy Burns for thirteen years. She stated;

“John W. Burns has been abusive to his wife during the entire time I have known them. He often beat and pounded her, she has come to my house at midnight, often earlier to escape a beating. He has not supported her since I have known them. She made a living by taking in sewing. . . He often swore at his wife and struck her in the face and blackened her eyes. He would frequently pull hand full of hair out of her head. On a number of occasions, he threatened to kill her. His treatment finally became so bad bad she was compelled to leave him for her own safety. ”

Initially, he kept possession of the house, but later moved to Newton. After he moved to Newton, Lucy returned to the Sedgwick area to be near her son and daughter-in-law. During the time of separation, and even prior, Lucy Burns had provide for herself working as a seamstress. Witness statements in the pension file noted that the only thing that her husband had provided for her in thirteen years was a cloak.

Family members from Illinois also sent statements.

Statement from William Roberts.

In all the statements Lucy Burns was described as “a woman of good moral character,” who although living separated from her husband for her safety, was his lawful wife. She never divorced him, or married another. She was deserving of the widows pension.

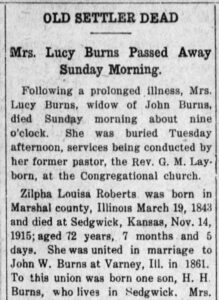

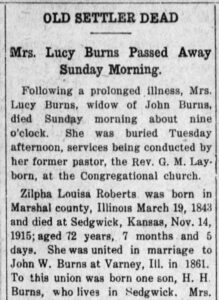

Lucy Burns died 14 November 1915 at the age of 72.

Sedgwick Pantagraph, 18 November 1915

“The Old Soldier“

John Burns was not alone among Civil War veterans from suffering lingering effects of what he saw and did during the war. Witness statements from people that knew him and his wife since childhood do not hint at violent behavior prior to the mid 1880s. So what caused John Burns to become an abusive husband.

Some Civil War historians have looked into the idea that some of these men may have suffered from what today is labeled PTSD. In the early 20th century, however, men with suffering from PTSD were diagnosed with derangement, a feeble mind, insane. How to care for them was a complete unknown other than to send them to a hospital that could handle the insane.

Burns was not the only Civil War Veteran to be declared insane. One historian, Eric Dean studied admissions to the Indiana Hospital for the Insane and discovered 291 Civil War veterans were admitted many with violent and erratic behavior or acute panic attacks and suicidal thoughts. Dean attributed this to the trauma experienced either in battle or in prisons. For many “old soldiers” of the Civil War, it never quite ended. Even though he returned physically, John W. Burns’ emotional injuries took a toll on both himself and his family in later years.

Sources

- Burns, John W. File. The John C. Johnston Collection of Civil War Pensions, HCHM Archives.

- Evening Kansan Republican: 24 April 1902, 25 April 1902, 26 April 1902.

- Sedgwick Pantagraph: 18 November 1915.

- Information on John W. Burns’ Civil War Record courtesy Baxter B. Fite III on Find A Grave and via e-mail with author.

- Horwitz, Tony. “Did Civil War Soldiers Have PTSD?” Smithsonian Magazine January 2015.

This blog post is part of a Heritage Grant from Humanities Kansas to digitize the John C. Johnston Civil War Pension Collection. As part of the project HCHM, seeks to tell the stories of these men and their families.

Humanities Kansas is an independent nonprofit spearheading a movement of ideas to

empower the people of Kansas to strengthen their communities and our democracy. Since

1972, our pioneering programming, grants, and partnerships have documented and shared

stories to spark conversations and generate insights. Together with our partners and

supporters, we inspire all Kansans to draw on history, literature, ethics, and culture to enrich their

lives and serve the communities and state we all proudly call home. Visit humanitieskansas.org.