by Kristine Schmucker, HCHM Curator

Harry Lum, probable friend to all, but close to no one, was a man that lived on the edges of the Newton community, providing a much needed service as “our good laundry man” for close to 30 years. He also had the distinction of being Newton’s first, and for many years, only person from China.

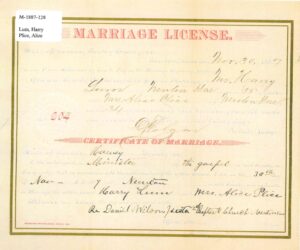

In 1880, 26 year old Harry was a miner in Humboldt, California. At the time, he was living in the household of Po Bar with a group of six other men, all from China. Harry must not have enjoyed mining as within three years he was living in Newton, Kansas. He married 22 year old Beckie Swader on May 29.

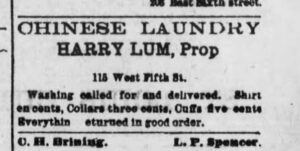

Chinese Laundry: Harry Lum, Prop.

In January 1884, the Lums opened a “new Chinese laundry” in Newton at their home at 116 W 4th. The Weekly Democrat noted that he “comes well recommended, and guarantees satisfaction.”

“Tired of ‘Wedded Bliss.”

Shortly after their marriage, the Lums began to have trouble. The Newton Daily Republican reported that “Harry Lum, the celestial who presides over the washee [sic] house on West Fifth street, has commenced suit for a divorce.” Rebecca “Beckie” Lum, described as a “lady of color,” was accused of “infidelity, abuse, gross neglect of wifely duties, frequent absences from home and finally abandonment” when she went to Sterling and had not returned “to his knowledge.”

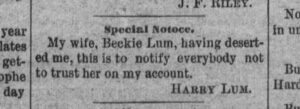

By December 1886, the marriage was over and Lum put a notice in the Newton Daily Republican indicating that Beckie Lum had deserted him and “not to trust her on my account.”

A year later, Lum married Alice (or Alize) Plice. Alice, a colored woman born in Kentucky in 1853, was also divorced from her first husband, Abraham Taylor, of Sedgwick County.

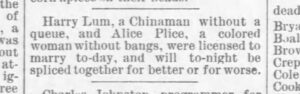

The Newton Kansan described the marriage ceremony:

“Harry Lum, a Chinaman without a queue and Alice Plice, a colored woman with out bangs, were licensed to marry to-day.”

There are brief mentions of Harry in the late 1880s. On November 10, 1887, the Newton Kansan reported that a drunken soldier went to Lum’s laundry and “raised ‘peculia hellee’ to use the language of the excited Chinaman” [sic] when reporting the crime. He was also mentioned in the obituary of Mrs. Lucy Russell, who was “dearly loved and greatly respected by those of her race,” and the mother of his second wife Alice.

“Renounced Allegiance to Chinese Empire”

The Newton Daily Republican reported in February 1889 that Harry Lum “our good laundry man . . .who was born and reared in the Celestial Empire . . renounced allegiance to Chinese Empire” and became an American citizen. The editor noted that Mr. Lum “has always borne a good reputation and will not abuse the privilege this day conferred upon him.”

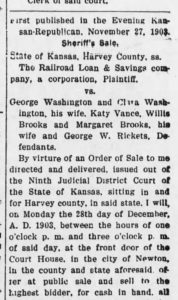

Even though Lum became a US citizen, he was still subject to the anti-immigration laws focused on the Chinese in the 1880s and 1890s. The Weekly Republican reported in the November 18, 1892 issue that “Revenue Collector McCanse . . . was here to secure a photograph of Harry Lum, our sole Chinese resident.”

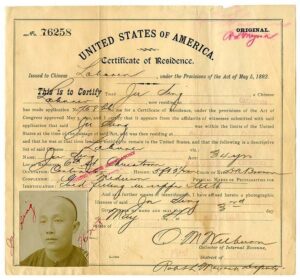

In 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act was enacted, however it was only valid for 10 years. The Geary Act in 1892 extended the exclusion of Chinese laborers for another decade. The Act required Chinese residents in the U.S. to carry special documentation—certificates of residence—from the Internal Revenue Service. Those who were caught not carrying the certificates were sentenced to hard labor and deportation, and bail was only an option if the accused were vouched for by a “credible white witness.”

An example of the required Certificate of Residence. Although this is not Harry Lum, it is an example of the document he would have carried.

In the spring of 1892, Harry suffered a painful accident. While ironing clothes for the Clark Hotel, two of his fingers got caught between the rollers causing a severe injury. The Evening Kansan noted “it will be some time before he is able to resume work.”

“All old scores are blotted out and friendships renewed”

A reporter from the Newton Daily Republican took some time in February 1894 to interview Lum about the Chinese New Year. During the holiday, “all old scores are blotted out and friendships renewed.” According to Lum, “the Chinaman who does not forgive a fellow countryman during these two weeks is a black sheep and all other Chinamen turn their backs up on him.” Lum noted that “like white men, many Chinamen get hilariously full on New Years and paint the town a bright crimson hue.”

Lum, however, celebrated the holiday like Christmas and had “dispensed with the insignia of all devout heathen . . . and follows the custom of his brother Kansans and is strictly temperate.” The editor closed with this description of Lum; “he has an idea that it is a capital offense to drown one’s senses in Kansas bug juice and he will neither drink whisky nor hit the opium pipe.” (Newton Daily Republican, 6 February 1894)

“A Little Gambling”

Lum apparently enjoyed gambling. The Wichita Star, August 1888, noted that Lum, “the christainized celestial from Newton was taking in the races to-day and betting his money allee samee like white man.” [sic]

Gambling also brought trouble to Harry. This was the case in August 1900, when Lum reported a robbery.

“Frank Weston, a gentleman of color, had procured a sum of money from him in a manner not prescribed by law. It seems there was a little gambling device operated in a shed back of the laundry.” At the end of the evening. Lum was counting his winnings when “Weston grabbed a handful of silver, alleged to be $20 and forthwith made his escape.” Weston was arrested. (Newton Kansan, 3 August 1900)

“Of Some Notoriety”

Harry’s wife, Mrs. Alice Lum, was more notorious in the Newton community. In 1892, she was found guilty of keeping a bawdy house and fined $50. Fights at the Lums were not uncommon. Abe Weston, also a Black man, was frequently involved. On March 26, 1892, the Evening Kansan Republican reported that Mrs. Harry Lum had issued a complaint against Abe Weston, who was arrested for assault. In return, Weston reported that Mrs. Lum kept a bawdy house and as a result she was arrested.

In 1907, Lum’s was the site of a shooting. John Allen shot Frank Jordan, both Black men, in the home of Lum. This gained statewide attention.

The Lum’s home was again the site of a drunken brawl in 1909 during which “Joe Rickman stuck his stiletto into Arthur Childs.” The reporter observed that “it had to be said to the credit of Harry that he does not seem to have participated to any great extent, if at all.” (Evening Kansan Republican, March 11, 1909)

What happened to Harry Lum?

In 1902, Lum sold his Newton business to another Chinese man, Shung Lee, and worked at Peabody during the week and spent Sundays in Newton. This business arrangement apparently did not last long. Shung Lee was not mentioned again and Lum returned to Newton to oversee the business.

Harry Lum’s exit from Newton seems to have passed without notice or comment. On December 28, 1910, Harry Lum and wife sold Lot 20, block 13, in Newton to Mary O. Grant for $1300. Shortly after that an announcement in the paper noted that Mrs. Harry Lum was moving to California, where she likely lived for the rest of her life.

A Mrs. Alice Lum died March 17, 1915, and was buried in Evergreen Cemetery, Oakland, Alameda Co, CA. She was 62. It is possible that this was Harry Lum’s wife.

Harry Lum, born in China in 1852 to Ward Lang Lum and Lara Lum, Newton’s “good laundry man, ” disappeared from the record after 1910-1911. A notification of Harry Lum’s death, or a place of burial has not been found.